The crowd gathered inside the small, rural schoolhouse. It was Cuba. 1950. And poverty and malnutrition were rampant. Already, the situation had become desperate, and childhood mortality rates continued to climb, particularly in rural areas like this one.

To make matters worse, the recent heat wave was severely affecting the milk production of the cows. Everyone had an opinion about how to turn things around. Some argued that the cows’ diet needed to change. Others said that the cows needed to stay out of the tropical heat to hydrate. One plan after the next was offered as the best solution to the troubling milk problem.

In the meantime, back at the schoolhouse, a tall American suddenly stood up from somewhere in the middle of the crowd. At the time, no one could have imagined the impact that his words would later have on the country. For now, all he offered was the kernel of an idea. A preposterous, elaborate, brilliant idea.

“What we need,” he said, “is an entirely new cow.”

Who was this guy?

As it turns out, he was my paternal grandfather, Richard G. Milk, and his eccentric plan would eventually become a national legend.

From a young age, my grandfather had dreamed of traveling the world and making an impact. He was trained as an agricultural economist, driven by the desire to improve the living conditions of the people around him. And he was also a spiritual man. So, he became a missionary, and set off for Cuba, where he and my grandmother built a school and raised their five children (my father was the second of five).

On that humid day in 1950, Richard Milk’s idea was simple: breed a cow that could withstand the particular heat of the tropics, while producing nutrient-rich milk found in more moderate climates.

Already, he had asked an American university for a New England Holstein, which he bred on the farm where he worked.

But to really bring his plan full circle, he needed one missing ingredient. To get it, he wrote a letter to the government of India, requesting a Red Sindhi bull.

Crazy? Yes. But six months later a Red Sindhi actually arrived on a boat from India via Louisiana.

The Cubans thought, “this crazy Gringo might be on to something.”

Did it work?

Well, a few years ago, a friend of mine traveled to Cuba and found himself on a tour that highlighted important moments in the country’s tumultuous past. Among the more famous events in Cuban history, the tour guide shared a less well-known story. It’s the story of the “Cuban Cow,” the dominant breed on the island, unique in its ability to adapt to the rare conditions of tropical heat without compromising its milk production.

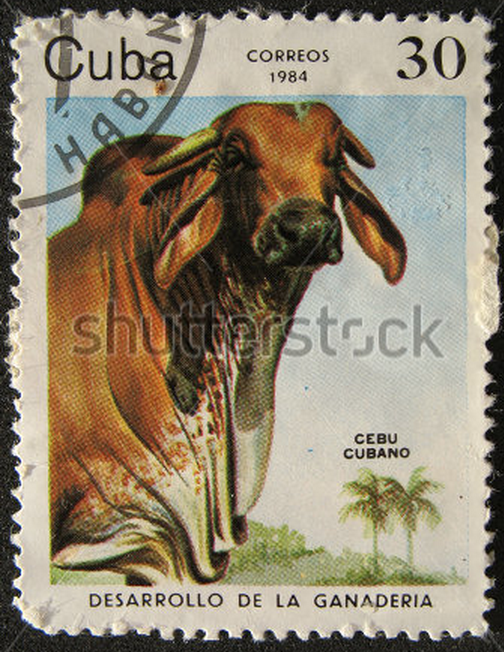

The guide credited the birth of the Cuban Cow to an American missionary, who 50 years prior had the audacity to bring this experiment to life. There’s even a stamp commemorating this special bovine breed.

When I think about this story, not simply as part of our family history, but from the perspective of an entrepreneur, ONE thing stands out prominently:

Here was a man who looked out at the world and saw it in terms of clearly defined needs and potential solutions, solutions that sometimes required highly unconventional measures.

This is the first mark of an entrepreneur: one who cannot help but see the gaps, the needs, the challenges, the problems, and immediately begins devising possible solutions.

Even as a missionary with no personal financial gain at stake, my grandfather was blessed with the finely tuned mind of a social entrepreneur. We might call him a “churchpreneur,” a man who was passionately driven to change and improve every difficult situation he came across, purely for social good. And, of course, not every idea was a winner. Far from it. But, then again, he did bring about the Cuban Cow, a highly innovative and unexpected solution to an urgent and serious problem.

“…It is not a pleasant thought to remind myself and others constantly that man for all his glory and wisdom has not showed the world how to feed her own. That as the world goes to bed each night two thirds of its souls are hungry. Yet I believe with all my heart that God wills that His children should have bread and that He would grant to us ways and ways of meeting this challenge if we would but let Him show us the way…”

— Richard G. Milk, 1950

My Peruvian Grandfather

At about the same time that Richard Milk was inventing a new cow, another entrepreneur was shifting into full gear.

It was a few thousand miles south of Cuba in a restaurant, packed to the rafters with Italian emigrants whose raucous laughter filled the room as music blared into the early hours of morning.

The country was Peru, the restaurant was the Panificadora Italo-Peruana, and the proprietor was my maternal grandfather, Julio Larnia.

Times were good. Business was bustling. But things hadn’t always run so smoothly. My grandfather was born in Italy. He had grown up as an orphan in a small mountain town near Genova.

One day, when he was a teenager, Julio Larnia snuck onto a ship headed to South America, and there began his real adventure into the world of entrepreneurship.

See, what Julio Larnia expected to find when he landed in Peru was very different from what he actually found. He had imagined a country full of opportunities, an easier and more fulfilling way of life. But he hadn’t counted on all the obstacles. He had no money. He didn’t speak the language. And he knew no one who could show him the ropes. For over a decade, he struggled and worked odd jobs to stay alive.

After many years of scraping by and saving the little money he could, my grandfather was finally able to open a small restaurant and bakery. His goal was simple. Create a home away from home for Italians in Peru.

He looked to his own early experience, identified a need, and came up with a solution.

To the extent that he was able, Julio Larnia wanted to improve the lives of his Italian countrymen while they were in Peru. More specifically, he didn’t want them to go through what he had been through when he arrived.

And so he built his little restaurant and soon added rooms in the back and created a monthly meal plan.

Whenever a new Italian arrived in Peru, penniless and searching, he was sent to Don Julio, where he’d be given homemade food and a place to stay.

Soon, he was importing Spanish olives, Norwegian cod, and all kinds of wines, cheeses, pastries and delicacies from Italy, including the latest Italian music. His little restaurant kept expanding and soon became the center of all things Italian in the North of Peru.

Out of this small realization that Italians needed a “home away from home,” my grandfather built a thriving business.

From birth, to being orphaned, to stowing away on an ocean-voyaging ship, to the streets of Peru, and eventually to running a business, my grandfather lived the life of an adventure novel.

His death followed in dramatic fashion when a burglar broke in, and cracked a brick over his skull as my grandfather tried to chase him down. Vibrantly, he came into the world, and with due fanfare, he left it. And in the interim, he showed us how to assess a need, find a solution, and create something meaningful along the way.

In my own experiences, and particularly when I talk to new entrepreneurs, I am overwhelmed by the simplicity of this first principle: the importance of identifying a genuine need is sometimes obscured by our enthusiasm to build our businesses, to launch our startups, to get our products to market.

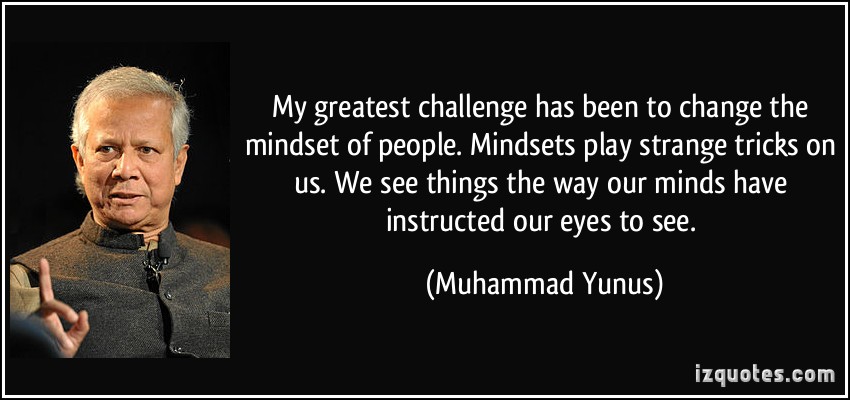

Nobel laureate and Grameen Bank founder, Muhammad Yunus, who I was so grateful to spend time with in Switzerland when we received a social entrepreneurship award from the Schwab Foundation, believes that identifying needs is central to the entrepreneurship process.

Yunus asks people to think about the problems they see around them, immediate needs that can be clearly identified. He then insists on prioritizing those needs by importance, starting with the ones that are most urgent. In that way, solutions are born directly of the needs themselves. For example, he says, “Suppose you put down unemployment. So why don’t you create a social business to solve the problem of five unemployed people?”

Real needs and real solutions.

Regardless of the business that you’d like to establish, whether it is to promote social change, build technology, push the boundaries of education, finance, industry, entertainment, or any other sector, at the most fundamental level, to succeed it should respond to some kind of underlying need.

While the need may not always be obvious—and some of the greatest innovations have responded to needs we didn’t even realize we had—an entrepreneur who takes the time to clearly articulate the specifics of that need, immediately secures an advantage.

So, let’s keep this real simple. Whether your business is already up and running or whether it exists only in idea form, challenge yourself to go back to the basics.